Why did the Industrial Revolution begin in Europe?

And what does the answer imply for us today?

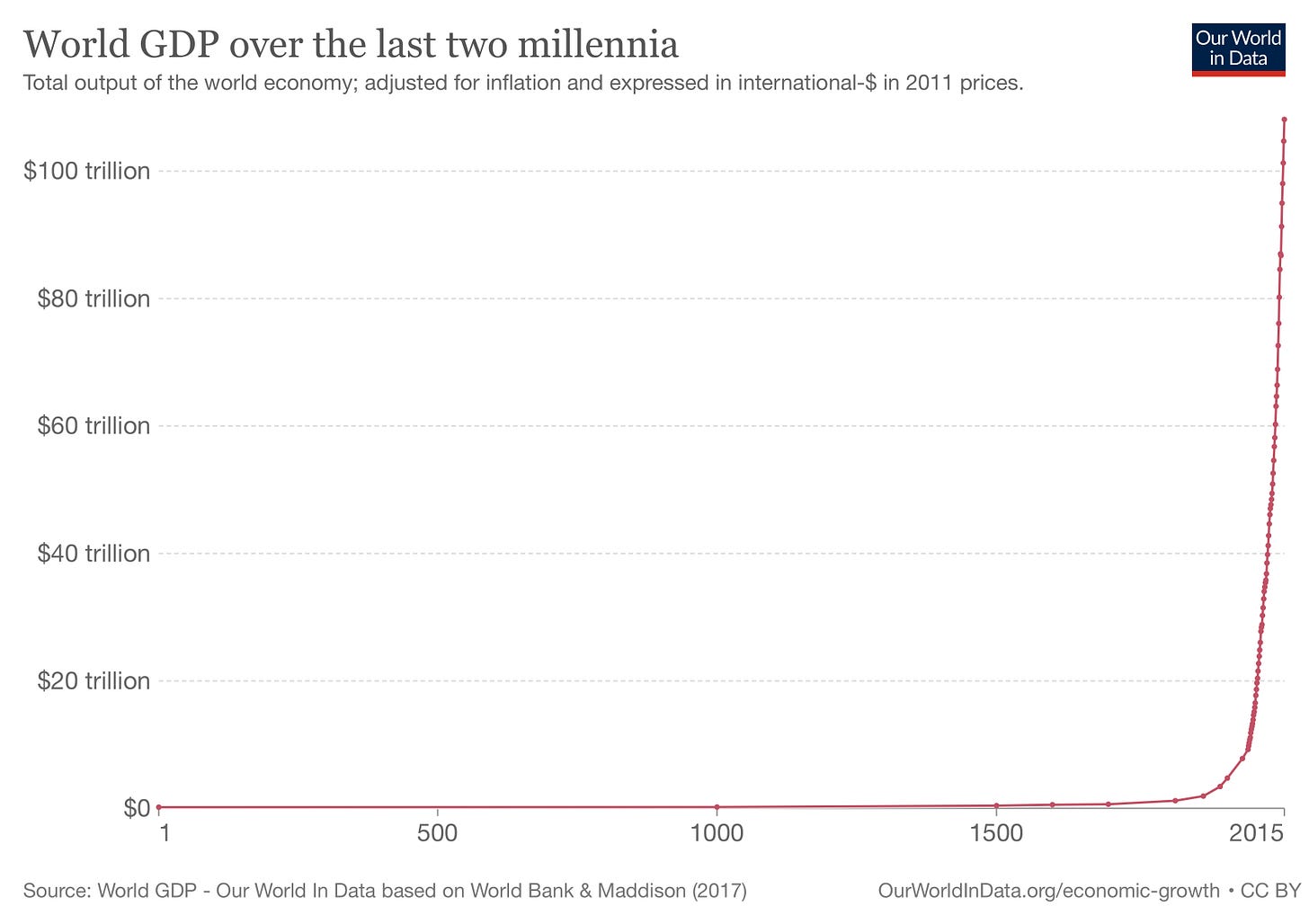

Everything changed with the Industrial Revolution. Up until about 1800, the economic history of the world had been a story of long-term stability and stagnation. Sure, there were periods of efflorescence and periods of crisis, but on the whole, both total output and output per capita were broadly constant across the long centuries. Then came the Industrial Revolution and a horizontal line suddenly became a vertical line. We can see this from the famous chart showing world output over the past two thousand years:

Since the Industrial Revolution, total output has increased about a hundredfold. This comes from a tenfold increase in population and a tenfold increase in output per capita. In other words, new technological advance meant that we saw not only rising output, but also rising living standards (as the gains in output far outpaced the gains in population).

This allowed the world to escape the Malthusian trap. Deriving from the theories of Thomas Robert Malthus (writing around 1800), the Malthusian trap says that any gains from technology would prove self-defeating. What would happen is that as living standards rise, population rises, and output per capita falls back down. Malthus argued that the population increased geometrically whereas the supply of food increased arithmetically. Because the amount of arable land is fixed, higher population means less arable land per person. With less land to grow food for the expanding population, this reverses the increase in output per capita and pushes it back down to subsistence levels. It’s a highly pessimistic theory, and yet probably described reality for most of human history. Before the Industrial Revolution, that is.

But why the Industrial Revolution began in the West - first in England, then spreading to Europe, then to North America? This isn’t an obvious trajectory at all. For much of human history, the wealthiest and most technologically advanced regions of the world were actually in the East - in China and India. Have a look at the chart below, which shows the global contribution to world GDP over two millennia. We can see that before the Industrial Revolution, Asia was the economic nerve center of the world. But after 1800, Western Europe and the USA took over.

So why did this happen? There is no shortage of explanations. Economists have tended to focus a lot on institutional factors. One of the earliest interventions in this field was Max Weber’s hypothesis that the “Protestant ethic” gave rise to capitalism in Europe. Nobody really accepts this today. Joel Mokyr points to the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment, which allowed for scientific breakthroughs. In a similar vein, David Landes argues that European countries had a political culture more favorable to openness and innovation. More recently, in a book called Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argue that England had the advantage of both inclusive political institutions (especially after the Glorious Revolution, which checked the absolutist power of the monarch) and inclusive economic institutions (through extensive property rights).

The problem is, the institutional arguments don’t really hold up. I’m relying here on a marvelous book by Kenneth Pomaranz called The Great Divergence. Although over twenty years old now, Pomeranz’s thesis holds up. Branko Milanovic offers a succinct review here.

Pomeranz basically argues that on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution, China (and to a lesser extent India) actually had more favorable institutions than Europe - including through the protection of property rights and the development of markets. Indeed, China’s institutions seemed more in line with what was recommended by Adam Smith - respect for property rights, competitive and unified markets, low taxes, and low public debt. Europe at the time was still in the grip of feudal-style institutions, including by tying peasants to the land and restricting their mobility. Land was much easier to sell in China, the state interfered less in commerce, and there were well-developed and fairly free labor markets.

Taxes were also much lower in China. They were high in Europe basically to fund Europe’s war machine. Europe built up state capacity to support military capacity. This would turn out to be important for economic history. See the following chart from Thomas Piketty, which shows the rise in tax receipts among the different regions:

So given all this, let’s return to the question of why the Industrial Revolution began in Western Europe. Pomeranz gives a few reasons. One is proximity to coal, a particular advantage of England. China had coal reserves too, but they tended to be located in more remote regions.

But this isn’t the main reason. They main reason lies rather in Western Europe’s role in the Atlantic slave empire. The colonies and the slave trade were highly profitable - delivering a very high financial return of 7 percent a year. This was going to make Western Europeans rich - including in the new textile factories. But more importantly - and this is the essential point for Pomeranz - the slave empire allowed Western Europe to break out of the Malthusian trap. The Malthusian trap, remember, centered on inadequate land to grow food. The New World solved this problem for Europe. And because food and cotton were grown with slave labor, they provided cheap nutrition and clothing for Europeans, freeing them to leave the land and enter the factories. Without this, Europe’s development would be been stopped by a hard ecological constraint. Instead, Europe was able to maneuver an escape from the Malthusian trap that eluded China and India. As Branko Milanovic puts it, “Without the Americas, there would not have been (modern) Europe, nor the Industrial Revolution.”

Now, a lot of people don’t want to hear this. Because it suggests that the amazing technological development we have benefited from starting around 1800 was built on a grave evil. And indeed, slavery was an institution with an enormous footprint. At its peak, there were six million enslaved people in the New World. Here’s another chart from Thomas Piketty showing its scale in the Americas, reaching a peak during the very height of the Industrial Revolution:

This gets to another point raised by Piketty and Pomeranz (and also discussed in my book, Cathonomics): the industrial development of Europe went hand-in-glove with the deployment of massive military might all over the world, especially by controlling the seas. While China might have had better institutions, Europe had stronger militaries - the results of improved military technology developed in response to inter-state rivalries. And Europe became more confident in extending this military might across the world.

This is how Europe controlled trade in Asia - not through free markets, but through force. This goes all the way back to the Portuguese voyages of discovery in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Later, the English and the Dutch set up private companies that were given monopolies over trade with Asia - and the British East India Company managed to control the whole of India at one point (until this was taken over by the British state in the mid-nineteenth century). The European powers also forced China open to trade - including a ruinous trade in opium. And as the nineteenth century progressed, Europeans replaced their old slave empires with a renewed push for colonization in Africa.

All told, the colonial powers deliberately hindered economic development in their conquered territories, including by suppressing education. Through protectionism, they wiped out competition for final goods - most notably the suppression of the textile industry in India. They used the colonies as sources of cheap raw materials, and forced them to buy finished goods from themselves. They saddled them with debt, again hindering economic development.

It should be noted that all of this was taking place when Britain was promoting the virtues of free trade, liberalism, and open markets. Yet Britain only made this switch once the use of force had given it a clear advantage.

As a result, as Piketty notes, China’s and India’s share of global manufacturing fell from 53 percent to a mere 5 percent between 1800 and 1900.

This is the story of the “Great Divergence.” It’s a tawdry story that casts of a moral pall over the last two centuries of economic development. Only in recent decades have we seen sustained catching-up from the rest of the world - most notably in China, which is really taking its rightful place back at the center of the global economy. This catching-up only began in earnest after 1950, when formerly conquered and dominated regions regained political sovereignty.

What lessons should we take from all of this? One is that there is no case for triumphalism. Putting it simply, we developed on the backs on others, especially enslaved peoples. This gives rise to larger questions, chiefly: What debt is owed by colonial powers to their former colonies? What debt is owed to the descendants of enslaved people, who still face discrimination and economic marginalization? There is a certainly a moral responsibility to fund development in the world’s poorest countries. Perhaps there is also a case for reparations. At the very least, we need an open and honest debate about the skeletons from our past.

W European Germany had NO EMPIRE IN AFRICA, AMERICA OR ASIA to speak of in the 19th Century. They also had no role in the Slave trade. Nonetheless, they became an Economic/Military Powerhouse after Bismarck's 1870 unification.

Both Spain and Portugal had extensive New World colonies and involvement in the slave trade, but it was not in Southern Europe or South America where the Industrial Revolution began. Your dismissal of Weber's theory does not explain differences of industrialization within Europe.